The Cinema Museum

There's something incredibly special about the experience of going to the cinema. That initial moment of walking in from a hectic high street to a quiet, dim auditorium. Sinking down into the comfy embrace of your seat. The gentle and excited buzz of chatter through the adverts and trailers. The sharp focus that being in a darkened room in front of a huge screen provides. That magic moment you sometimes get when the screen widens before the main film. The expectant hush of a crowd as the first titles begin to roll. The collective and audible expression of shared emotion during the film - gasps, laughs, screams, whimpers, sobs and occasionally even applause. Basking in the afterglow as the credits drift up to the heavens at the end of the film.

Nowadays of course, cinema, as a way of spending your precious leisure time, competes against myriad other forms of screened entertainment: TV. Netflix. YouTube. DVDs. The vast depths of the internet.

But back in the 1940s, cinema was the main form of public entertainment. No TV. No Internet. In 1946 alone, in the UK, cinema audiences hit 1.64 billion (that's 1,640 million). That's a vast number of people going to the pictures. Since then there has been a massive decline, principally because of television; and by 1984 audiences had dropped off a cliff, to 54 million (though since then they've been gradually climbing, back towards 200 million).

A huge number of cinemas closed over the second half of the twentieth century. And that rich social, architectural and cultural history could all too easily have been lost with their closures. Fortunately, a few people had the foresight to save as much as they could, preserving that history for us.

And one of the very finest collections can be found at the fantastic Cinema Museum, in an old Victorian workhouse where Charlie Chaplin spent time as a child, tucked away in a corner of south London.

The museum's unique collection has been put together by Ronald Grant and Martin Humphries, and is the result of a life long passion for cinema. Starting as an assistant projectionist with Aberdeen Picture Palaces, Grant went on to work at the BFI, and the Brixton Ritzy, not far from the museum's current home. He and Humphries established the museum in 1986, and it moved from place to place until they settled at The Master's House in Kennington in 1998. It is maintained there thanks to Grant and Humphries, and a small and dedicated force of volunteers.

I went along to the museum earlier this week to have a rummage around, and to take a few photographs.

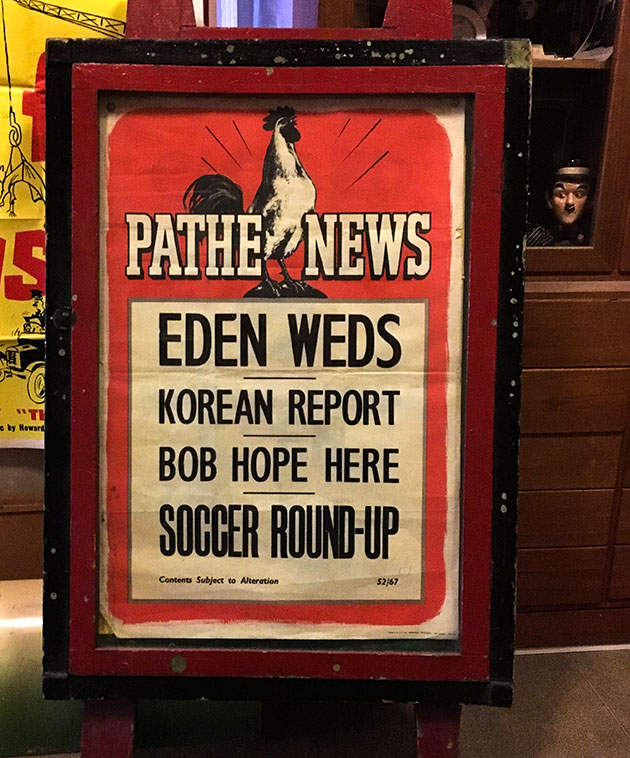

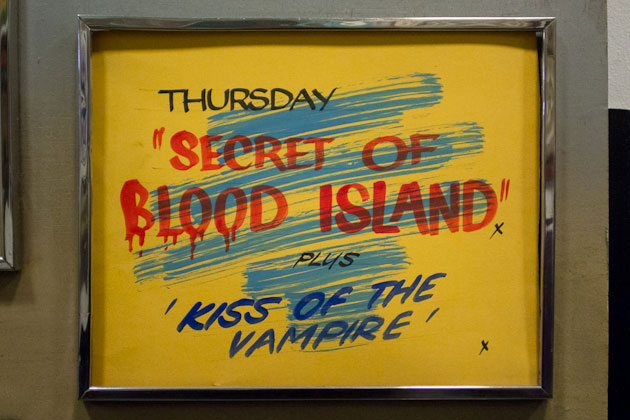

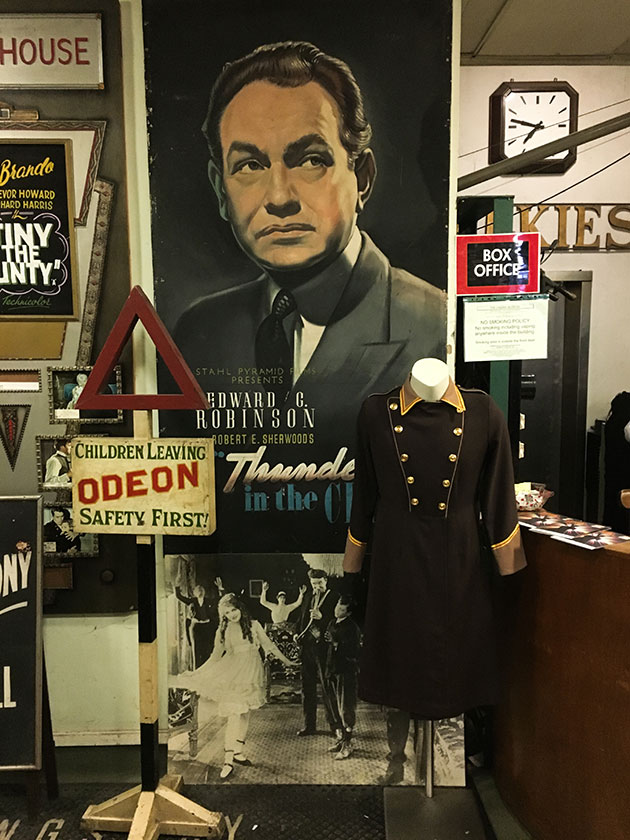

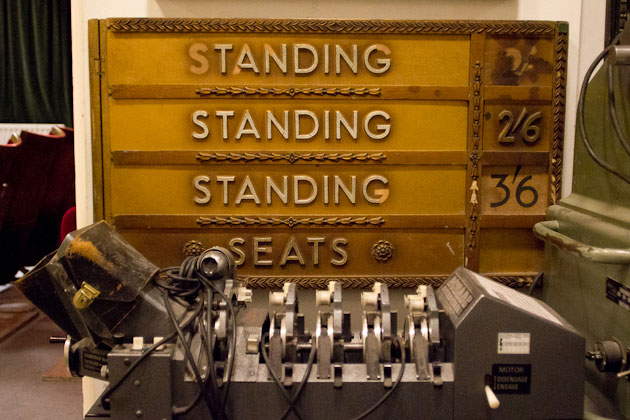

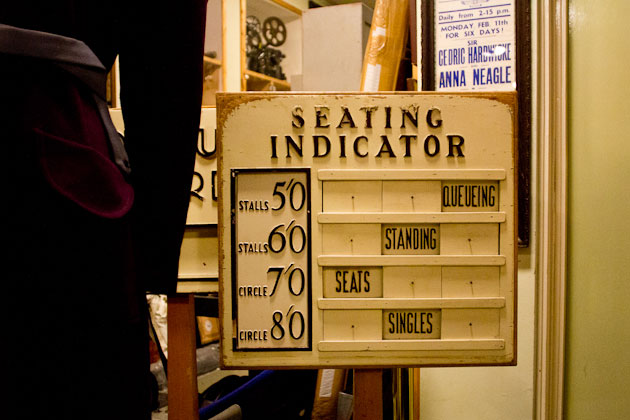

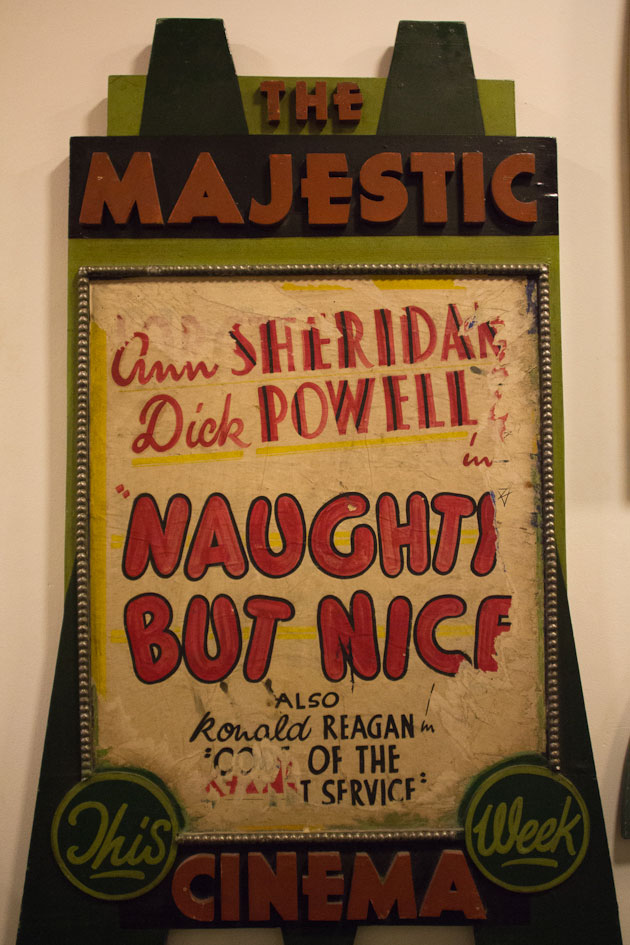

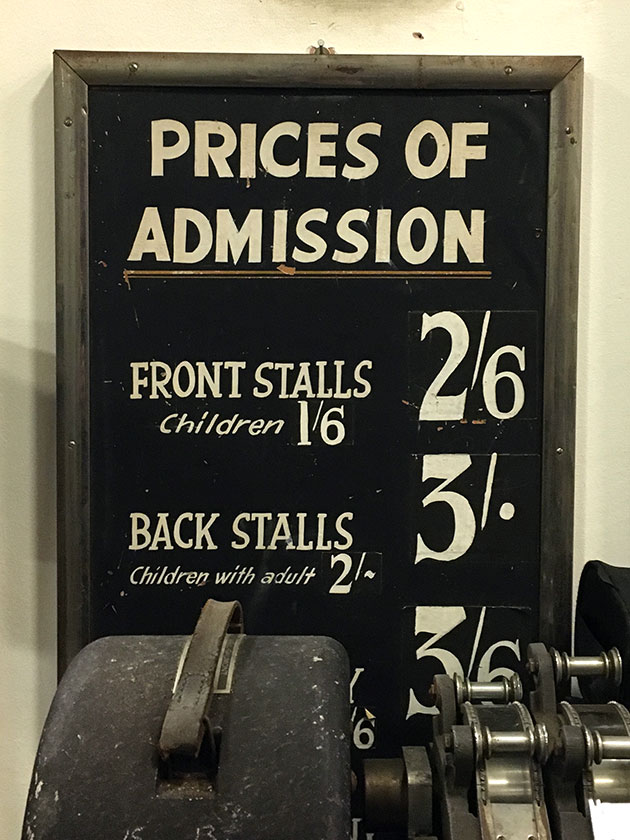

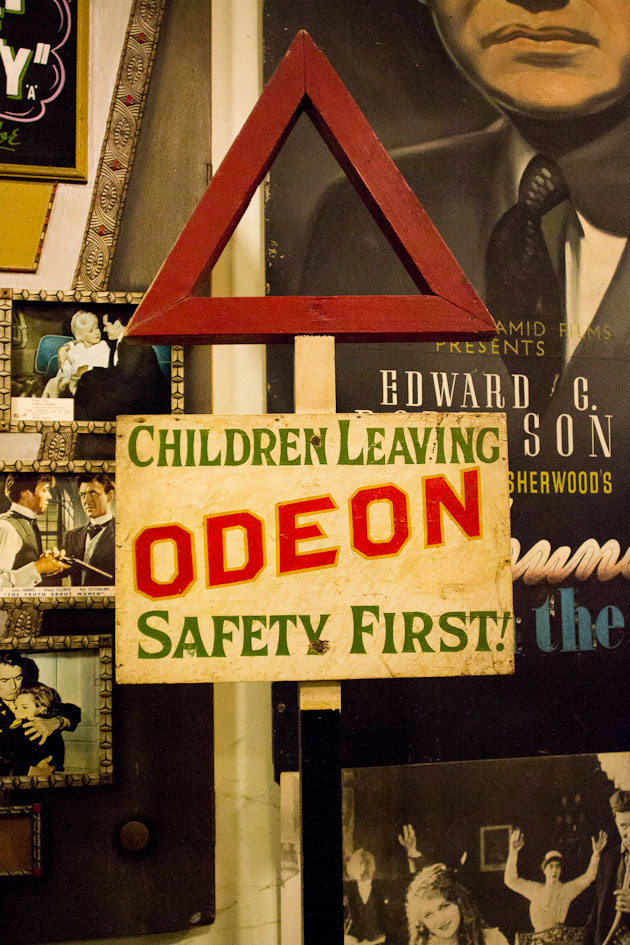

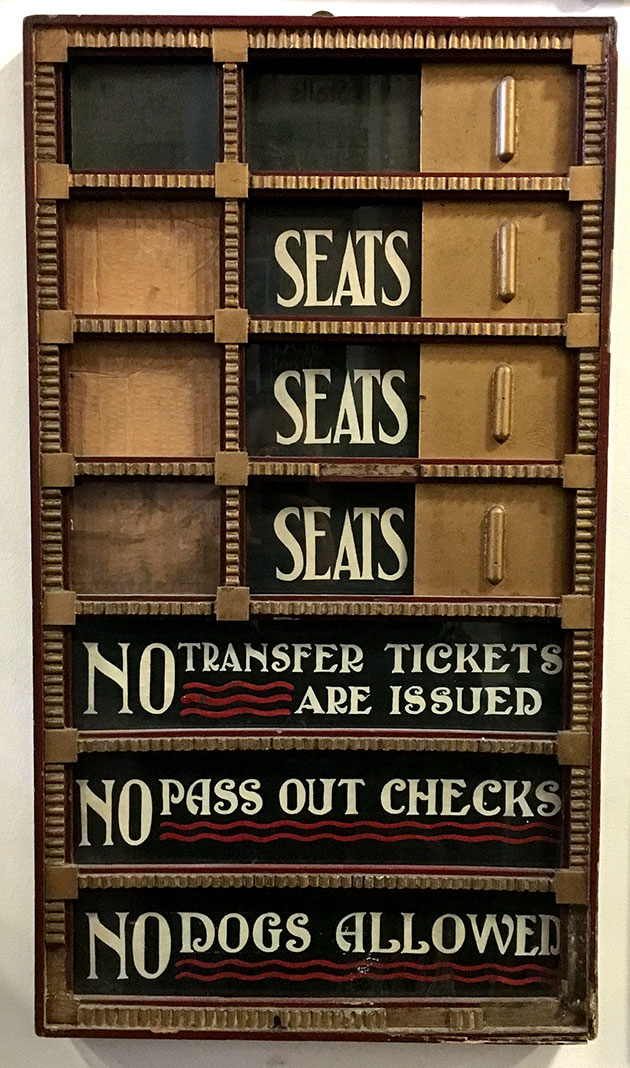

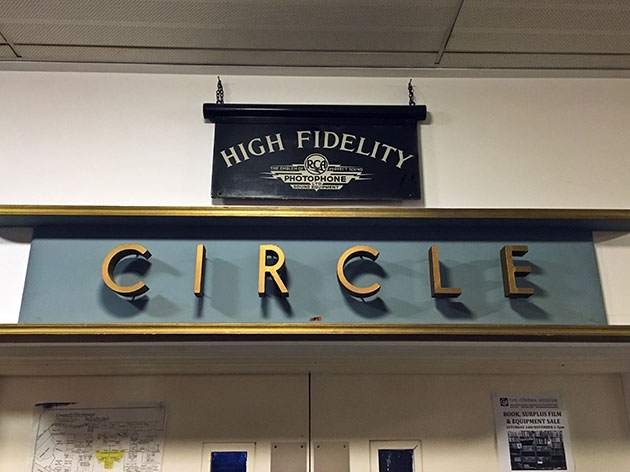

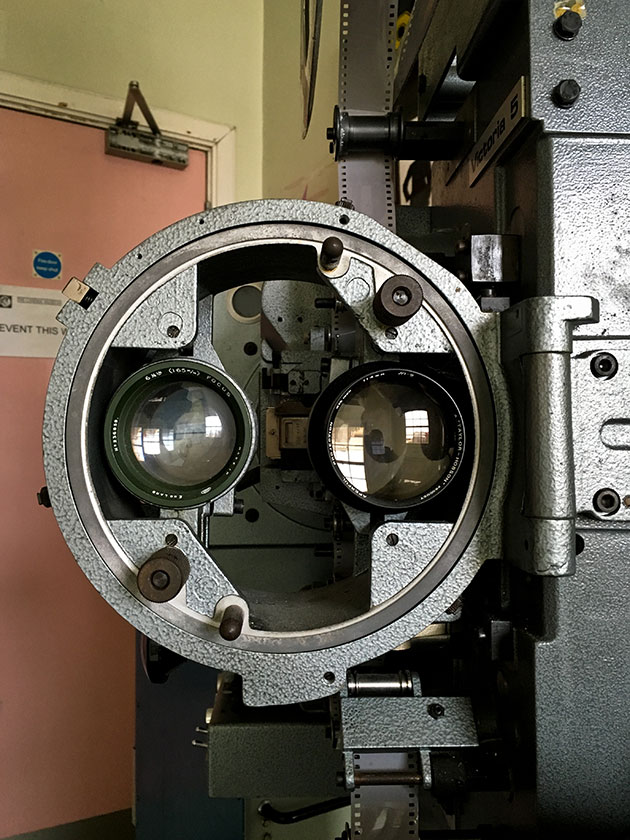

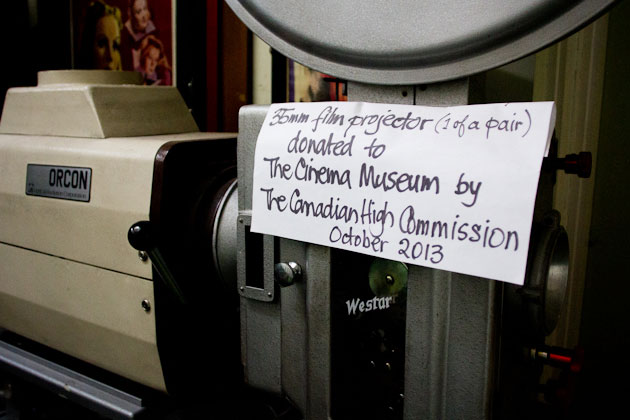

The museum is a glorious mix. You step through the front doors into a hallway stuffed to the rafters with an incredible collection of projectors and beautiful typographic cinema signs.

They also have other bits of cinematic ephemera: uniforms, equipment, playbills, newspapers, magazines…

On the ground floor there's a small screening room with a stunning set of original cinema seats.

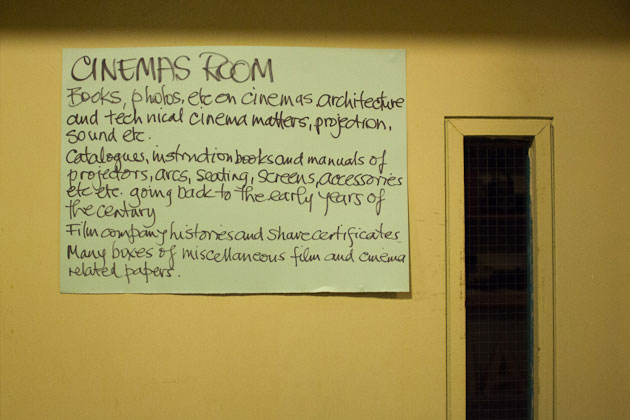

There's also an extensive library and archive, with more than a million photographic images; film sheet music; books; magazines; catalogues and other ephemera. They also have more than 17 million feet of film.

From there, you make your way through the building, and upstairs, past a huge Granada cinema sign, to a truly magnificent main room.

It’s quite the most incredible place. It’s preserving a vital part of our cultural heritage, and doing so with warmth and love. As well as providing an archive, they are open for pre-booked visits, host a programme of events, work with educational institutions, make items available for loan to other institutions, and are available as a venue for hire.

I went along to a screening there a few weeks back, and the atmosphere was really wonderful. It is absolutely worth a visit.

The museum is set up as a registered charity, and remarkably receives no public funding, relying instead upon donations. And, worryingly, they have no guarantee that they’ll be able to stay in their building beyond next year. For such a wonderful institution to have such an uncertain future is nothing short of scandalous. And peculiarly, it feels like the UK film industry haven’t really realised what a precious treasure trove they have right on their doorstep.

We can only hope that this marvellous place is secured for generations to come.

If you’d like to help, pop along to their Support page, or get in touch directly.